“Are you a communist?” a Dutch citizen asked me in a heated debate. I didn’t know how to react, I felt confused.

My name is Hristina Tasheva and I am 46 years old. I was born and educated in communist Bulgaria, but for 21 years I have been living in the Netherlands and working as an artist.

Arriving in democratic Western Europe as an illegal migrant and later granted Dutch nationality, I am still struggling to find my place in society.

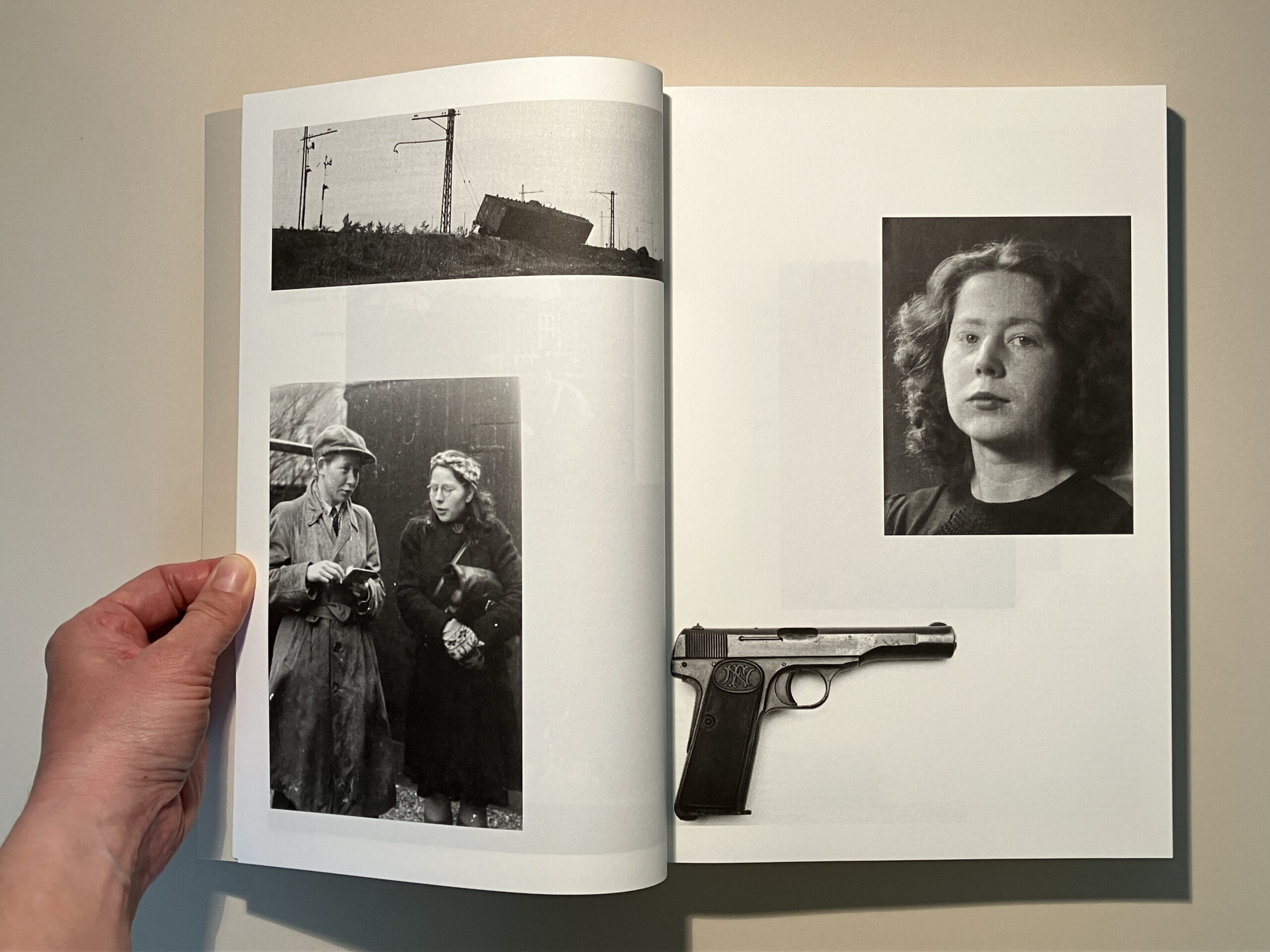

Taking into consideration the participation of the Dutch communists in the Resistance in the occupied Netherlands and their prosecution during WWII and the criminal deeds of the Bulgarian communists to realize the communist utopia in Bulgaria after the war, I asked myself ‘Am I seen as a victim (resistance fighter) or a perpetrator by the local people? Am I what they think of me?’

I have started an investigation of these historical events by ‘walking’ in the footsteps of the communists as a method of understanding the ‘other’. The information for my artistic study is drawn from the collective memory constructed in both countries: archives, literature, testimonies of victims and perpetrators, academic research, and my own experience and fieldwork.

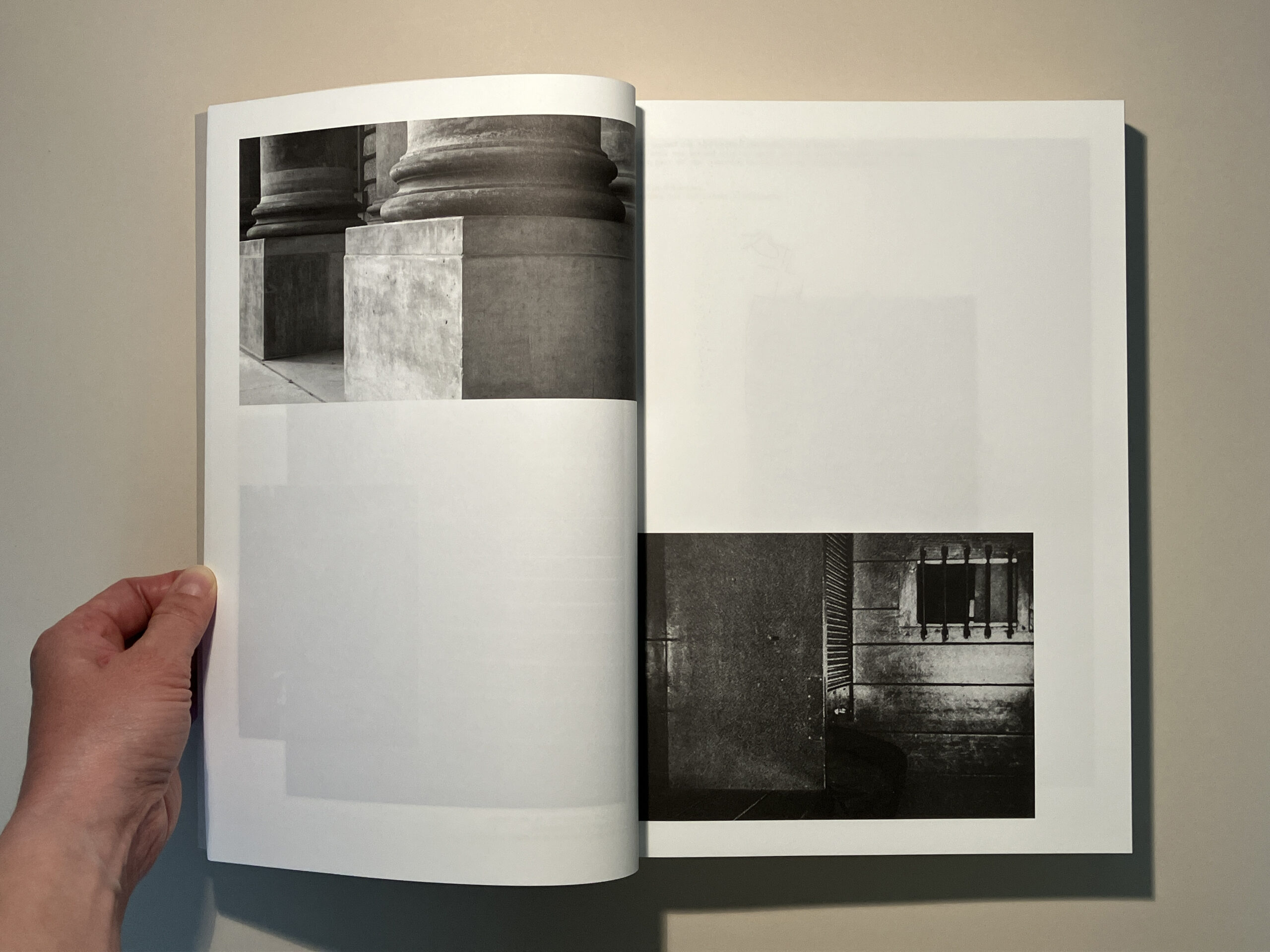

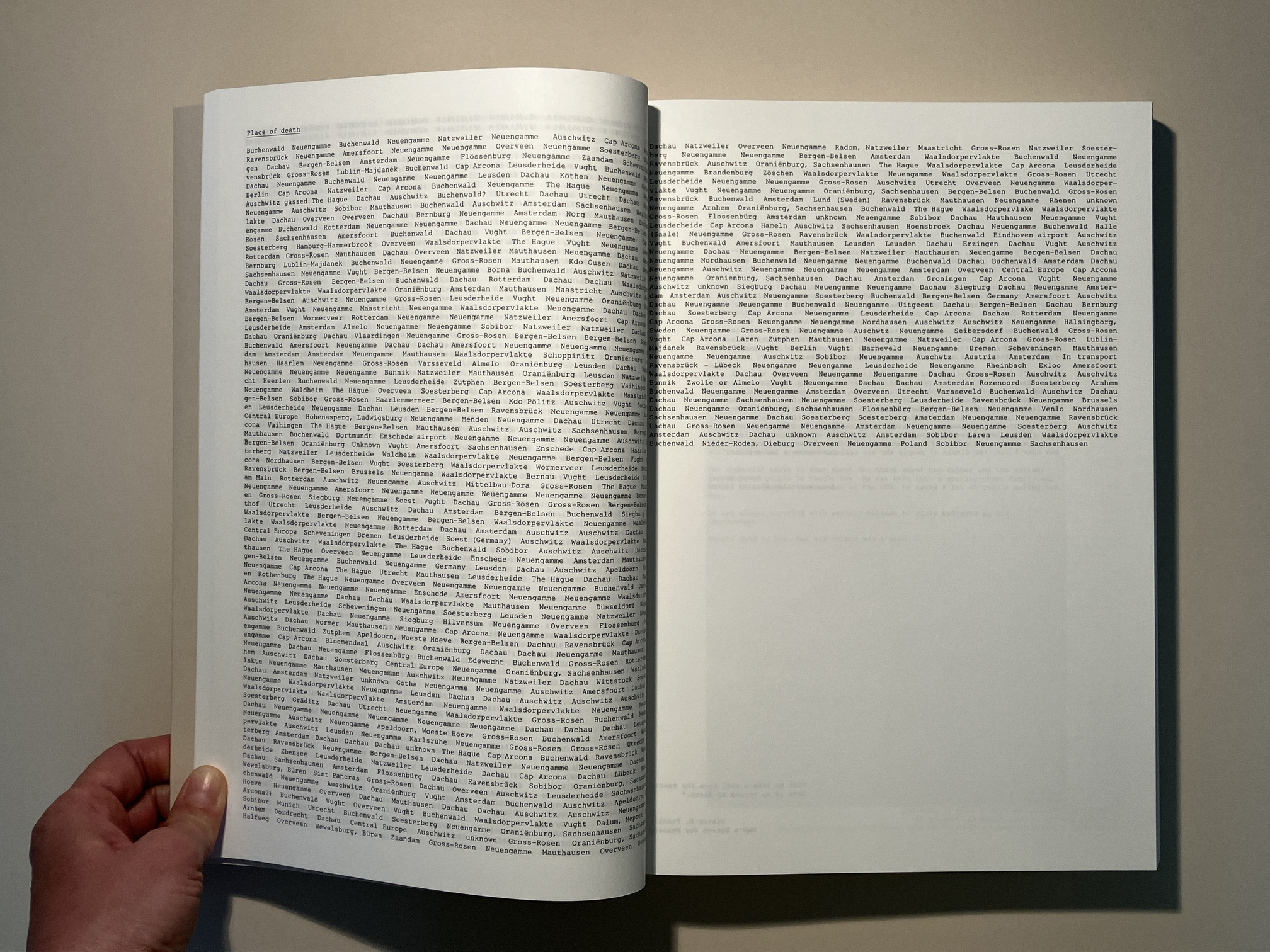

I took photographs at memorial sites at former Nazi concentration camps in the Netherlands, Germany, France, Poland and Austria, where many Dutch communists were murdered. I have also tried to find the locations of the communist concentration camps created in Bulgaria (today many of their locations are only approximately known), for whoever disagrees with the regime.

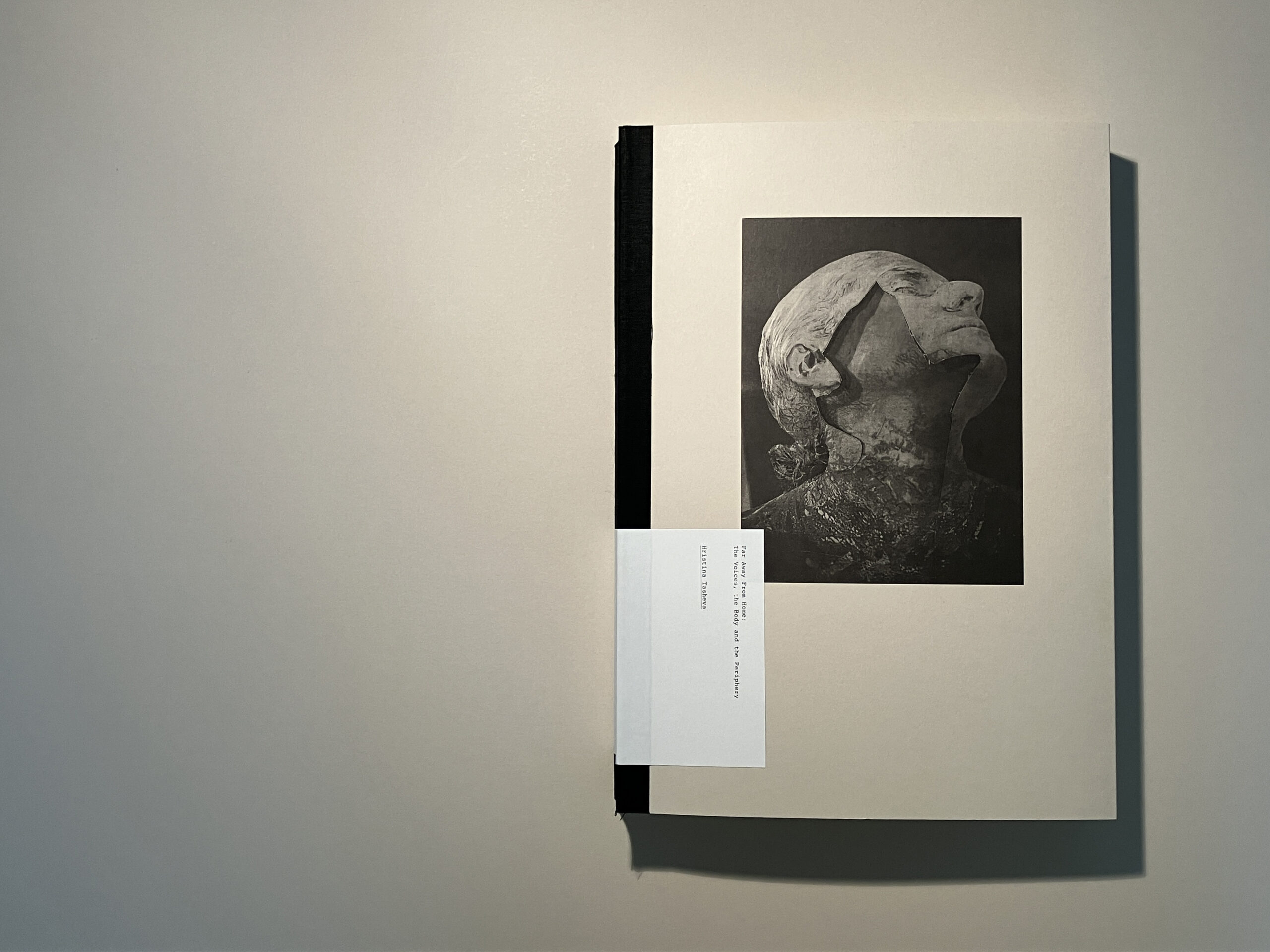

I visualised the result of my investigation through photography, drawings, and text in the project titled ‘Far Away from Home: The Voices, the Body and the Periphery’ self-published as an artist book at the beginning of May 2023.

Engaging with history and realising that what is remembered of the past is a construction that reflects on our idea of who we are, I wish to provoke a debate on our shared future in Europe: What does it mean to be seen as a ‘communist’ today or to define yourself as one? What is the common ground of ideologies like communism and National Socialism and what is their significance for the ‘average’ citizen of Europe? How do different societies organize their memory culture and are able to bring it into a critical perspective? How does the interpretation of history and politics of remembering influence the forming of our identities and our view on the future?