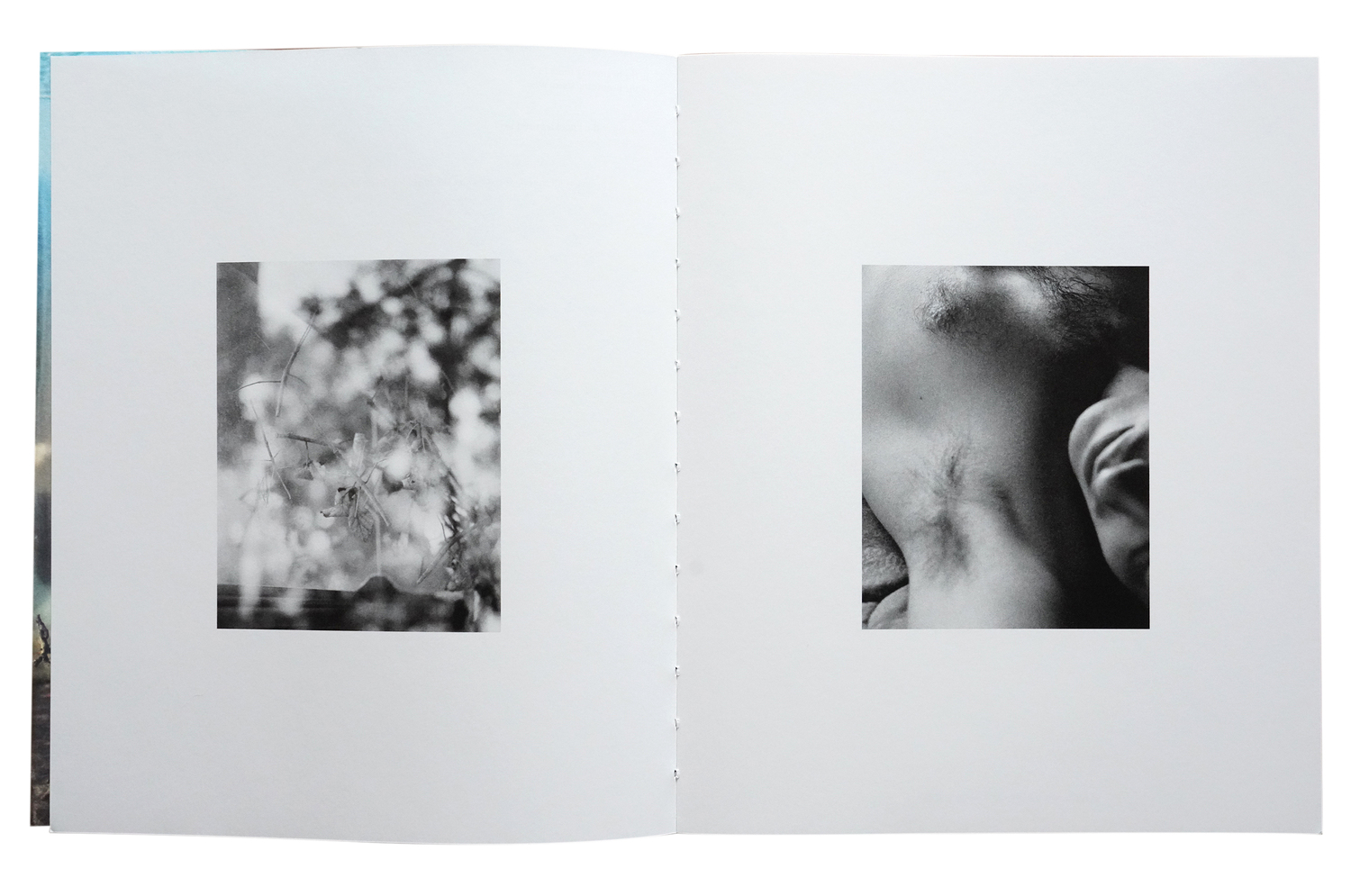

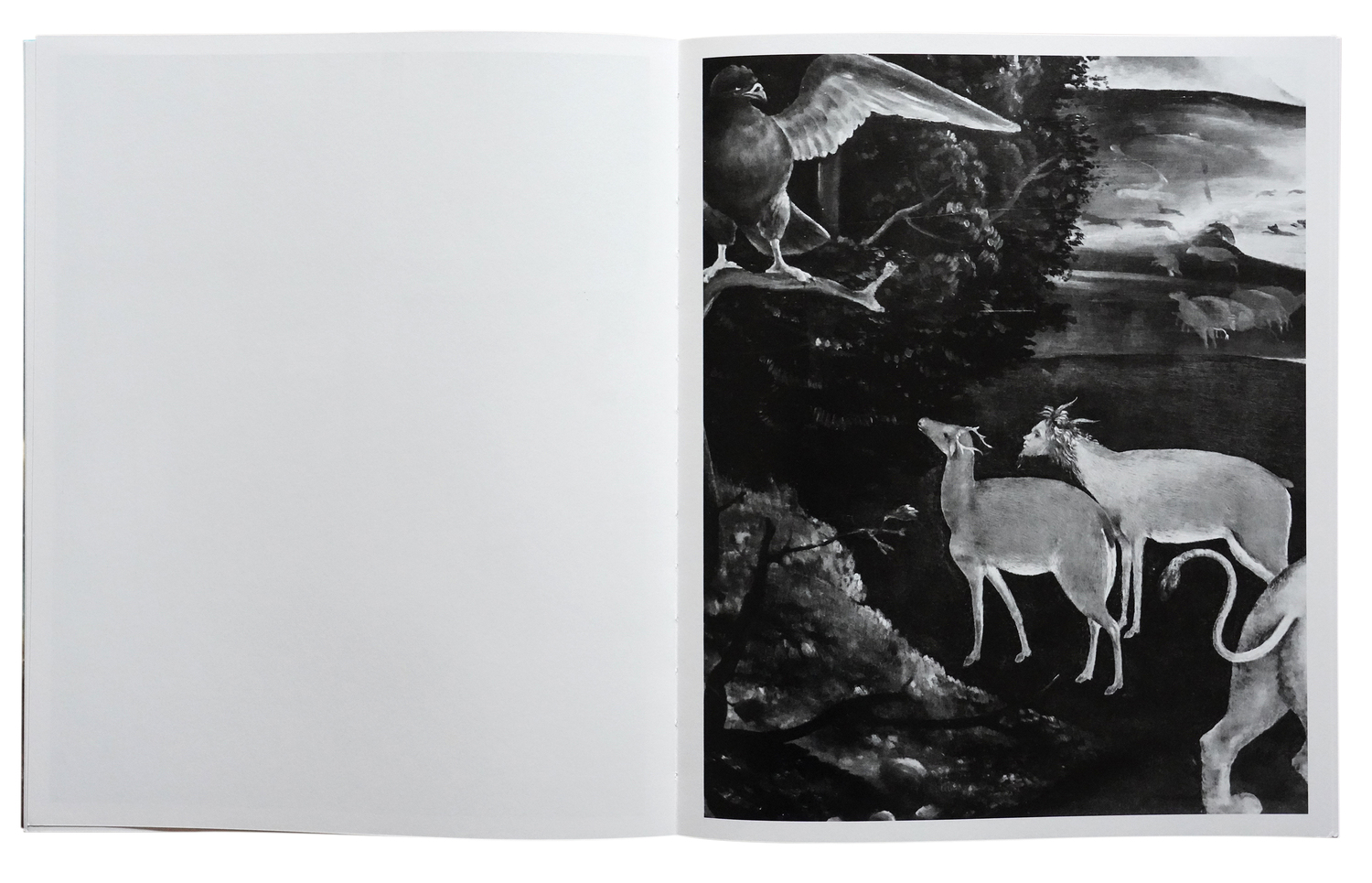

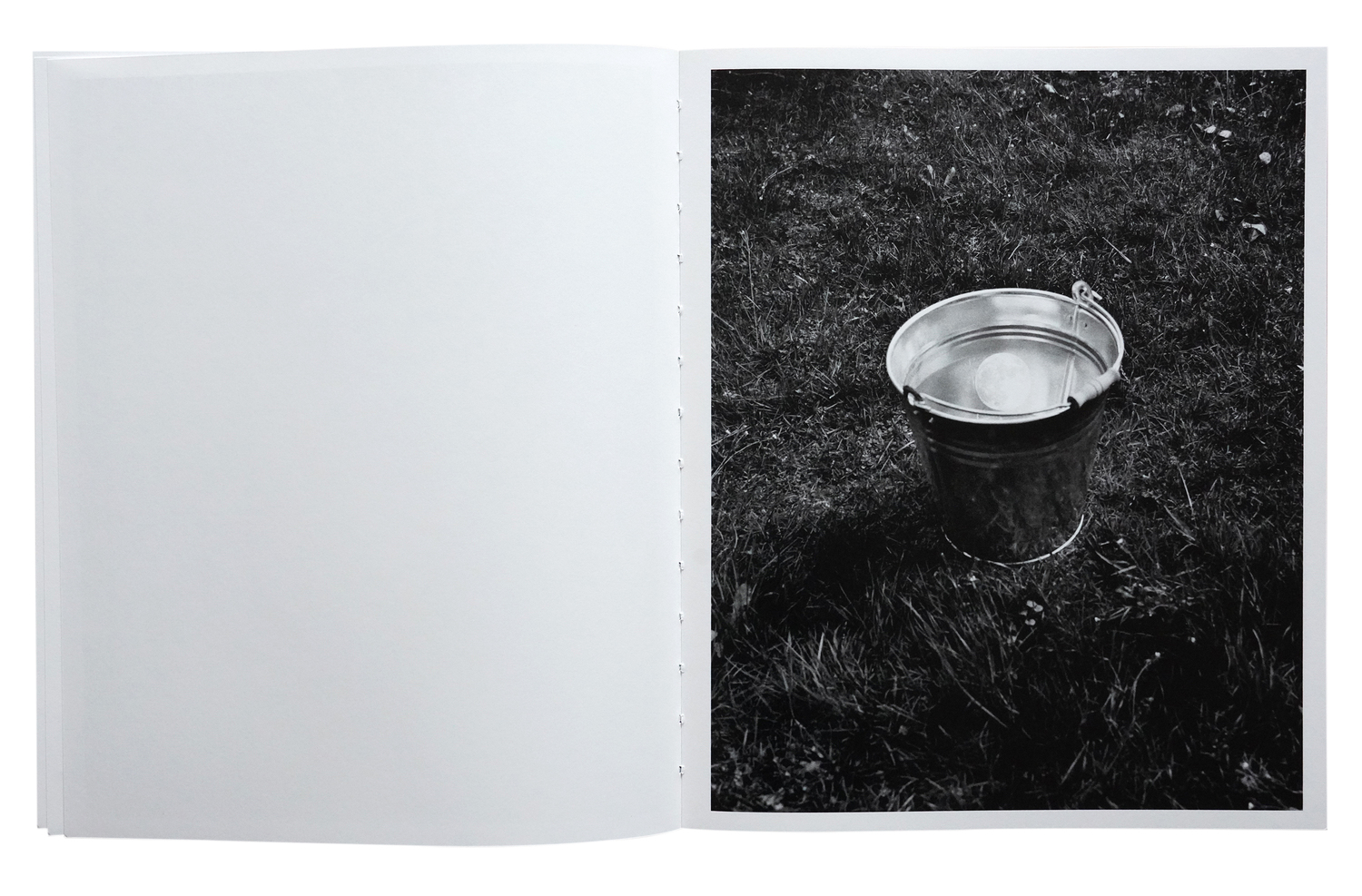

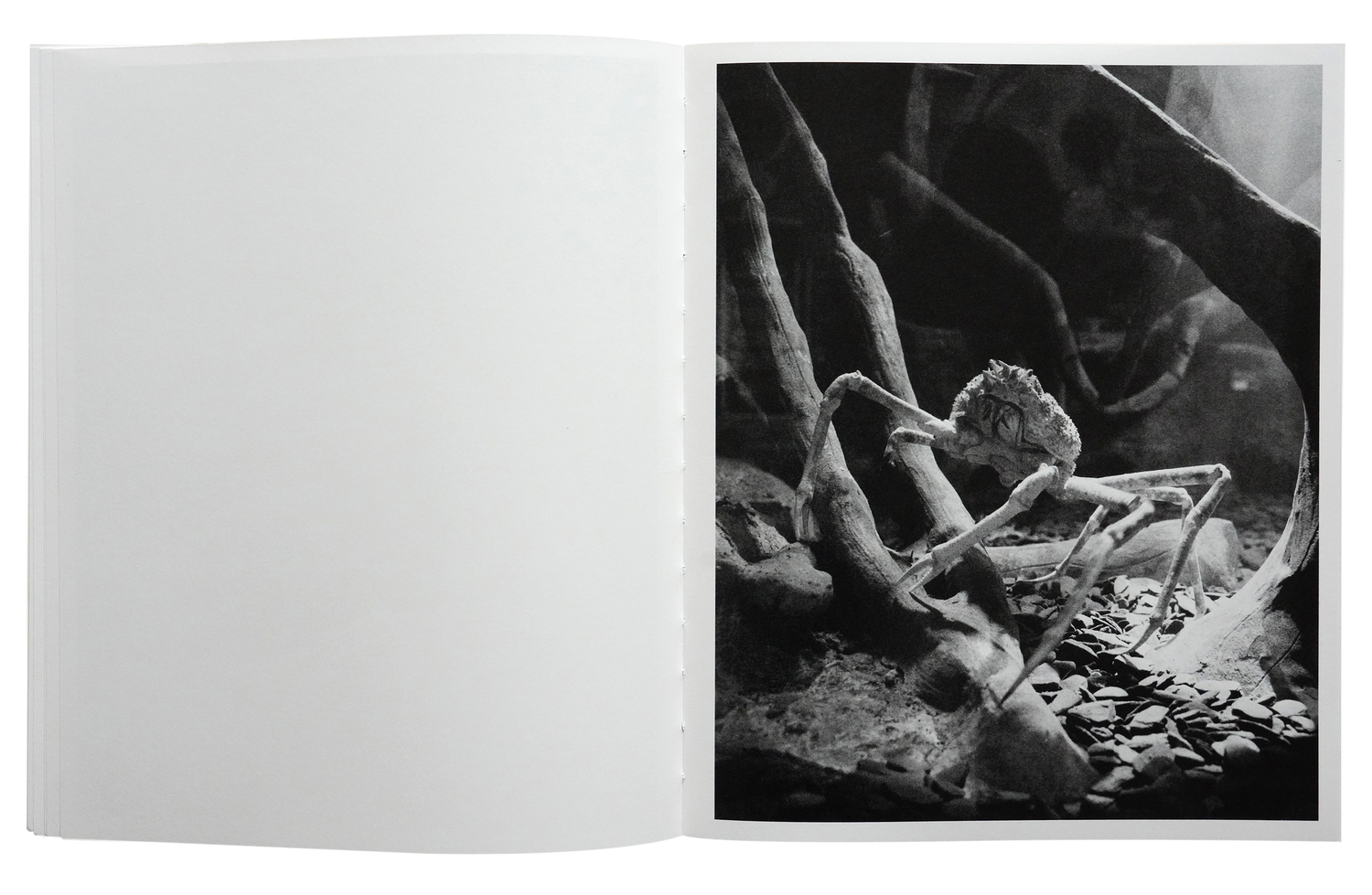

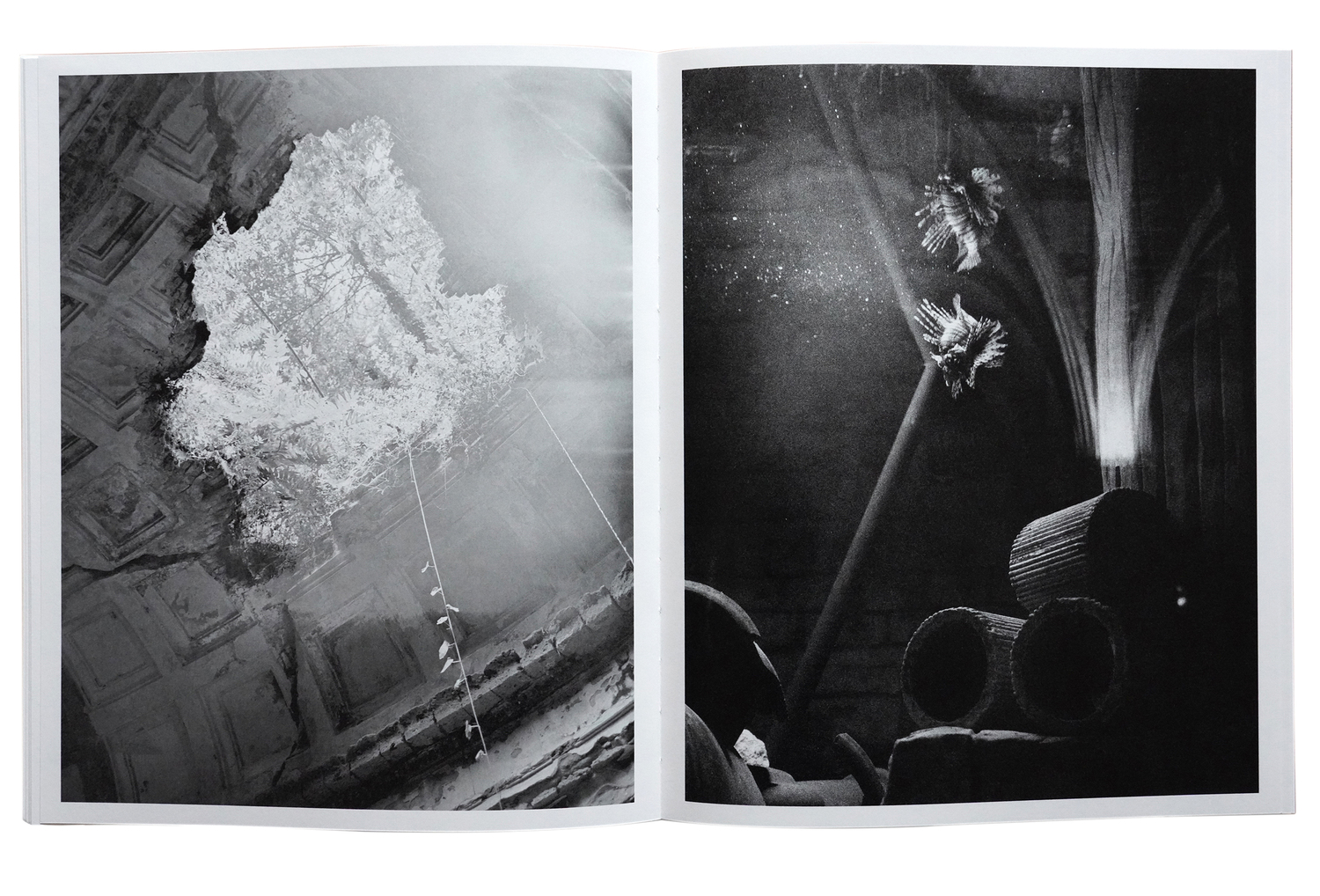

The cabinet looks empty — I take a step towards it, my breath fogging the glass. Keeping my gaze fixed, something amidst the vegetation faintly moves. Crawling, the stick insects manifest their presence like an apparition, they manifest themselves as some pictures do, emerging from certain dark recesses where they receded to nest. The animal that I am longs for proximity, snouts touching, but something — the camera? — keeps getting in the way. I try and try but my earth-sharing companions remain beyond my reach, they linger like ghosts on my film roll, trembling ever so slightly in the red light of the darkroom. I bring my snout close to the photographic paper and sniffle to pick up a scent to guide me back, but I am pricked by a sense of anticipated grief — are we able to preserve life only in its most mortifying form, petrified in museum cabinets and in photographs alike? And yet I return and show up for this encounter over and over again, love and longing making a fool of me, as I stay awake at night wondering if there really is a Dog.

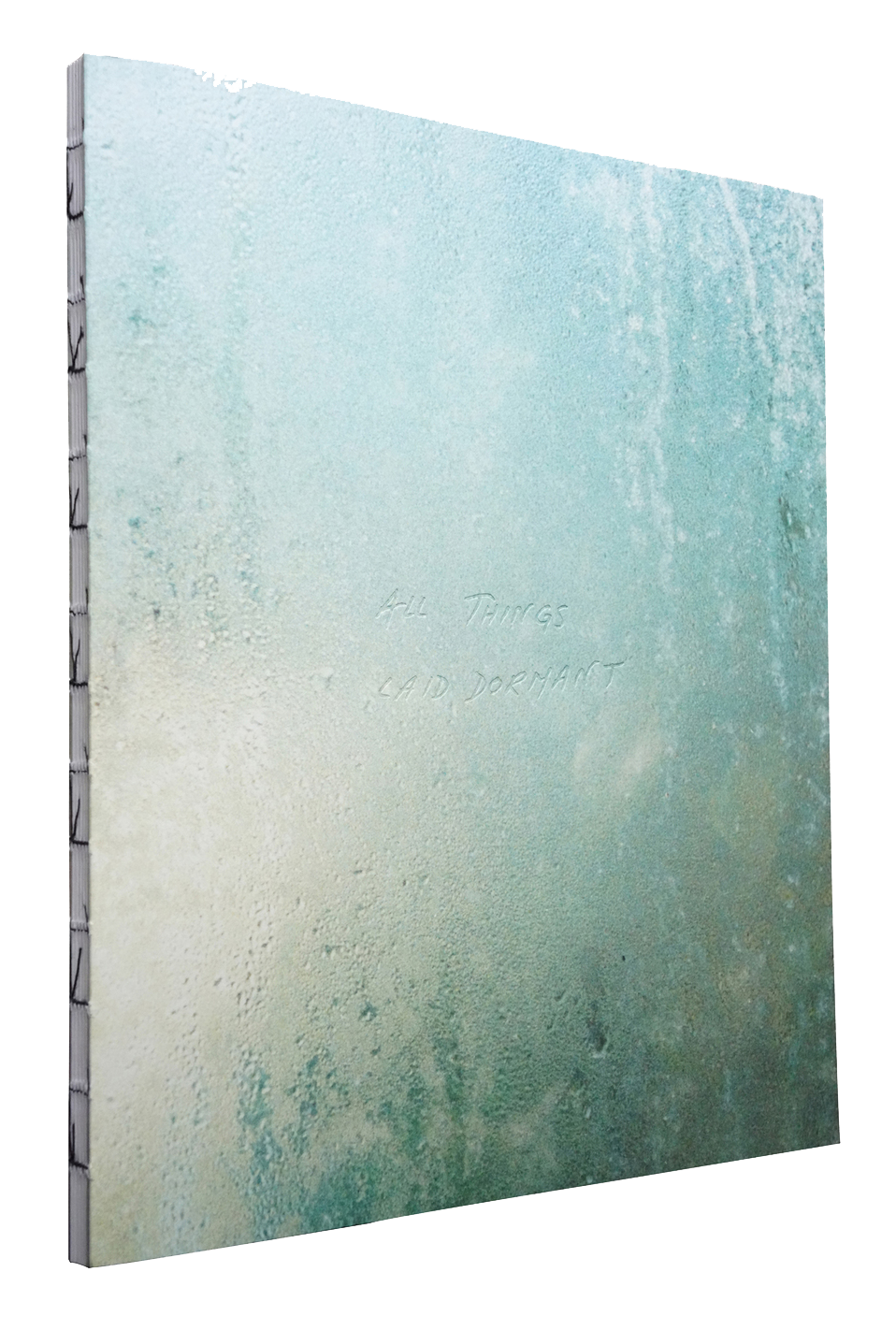

“All Things Laid Dormant” questions the ways in which we relate to other animals, the space they occupy in our personal and collective imagination, intra-specific coexistence, and the possibility of constructing new forms of kinship and intimacy in a context of mass extinction. Articulated through a series of encounters with the non-human world mediated by the implicit ambiguity of photography, that simultaneously facilitates and hinders contact, “All Things Laid Dormant” is both an ode and a lament, an act of love and an expression of mourning that embodies the suffering of loss and the desire to find a place and a sense of belonging within the fragile context of our time.